One of the most respectable ‘jobs’ in my view is being a startup founder. Building a complete business from scratch is the most difficult thing to do, with all uncertainties and personal sacrifices, without a brand name or proof backing your idea.

Being a venture capital investor is, to be honest, much easier. At Peak we see about a thousand propositions each year, we have chats with founder teams constantly, and we can look at some early metrics to see whether the target customers actually like the product… How beautiful can life be…

In the investment landscape, I have to honor one class of investors: the angel investors. Typically, they are willing to back founders with their own money, even before they can assess some early metrics, before the team is complete, and sometimes even before there is an MVP.

Looking at quite some propositions, we naturally talk to a lot of angels and see a vast number of angel-backed startups looking for follow-on funding. We recently had a session with our own investor base at Peak (consisting only of seasoned entrepreneurs) where we discussed the 8 most common pitfalls of angel investing. We thought it could be helpful for both angel investors as well as startup founders to share this list:

1. No real plan of the startup: yeah, duh… (but why do we still see this happening then?)

The success of a startup in our view not necessarily lies within the grand vision of world domination being pitched, or having an idea of a product or solution that all humans could benefit from. The success of a startup lies within the actual execution by the founding team. I believe one of the first questions an investor should ask is: “OK, I am going to wire the money, what are you actually going to do with it?” Assessing whether the team has the practical knowledge and drive to continuously execute, test, evaluate, adjust, and execute again makes the big difference. So don’t think I am talking here about the strategy for the next 3 years, I am talking more about the next three months or even weeks… The earlier-stage a startup is, the more practical it should be.

2. Too short of a time horizon (things take time – count on that: understand burn rate and milestones for next step)

We often see that angel investors expect a flawless execution after money has been wired. They are looking for a products new features being shipped as originally planned and a nice growth line in sales. In our experience, startups need about 2-3x longer to validate the market than most founders expect. A necessary pivot (or even 2 or 3) is quite likely in the early days. If the team can execute well and has the drive to find the right path, the startup is very well positioned. But: it takes time… And early investors should not expect the startup to be ready for VCs to invest within six months after they invested.

Hence, make sure the company has sufficient runway while operating in a cash efficient way. Think clearly which proof-points the startup should achieve for its next funding round and how long it might take (product ready, proof of customer acceptance, good customer engagement and retention, build-up sales pipeline, revenue traction, etc.)

3. Not knowing the team enough (everybody knows this, but why then still invest after only a couple of meetings?)

If you have had only 2 sessions with a founder of a company, he* might be a very good pitcher (but not an executer), he might have had a good day, or he might have been simply ‘exaggerating a tiny bit on the status of the company’.

In our view, it is always wise to really get to know the whole team very well: doing a sparring session on the strategy (product, market, tech, finance, whatever), engaging in a difficult discussion on a topic you might have a different view on, give them a relevant task to let them show that they can execute in a short period of time, and get to know them on how they stand in life as a person. In fact: you actually should work a bit with the team as if you are an involved investor already.

4. Too low on diversification – or the opposite: not picking stocks carefully enough – hoping spray and pray will do the trick

Startup investing is highly risky. In the classical theories about investments, diversification is often seen as the way to reduce risk (especially unsystematic risk). In startup investing, you still require to have sufficient companies in your portfolio (in our view 10 or more). However, investing in many companies can only be done easily if you can just wire funds without any advice and sell shares whenever desired (as with listed companies). Startups require more: they require attention to help a team through the very rough first stages, advice on difficult pivots, openings to your network, etc.

Furthermore, in our view in early stage investments, there simply are a lot of startups with lower chances of survival(based on many factors whether it is team, competition, product, network, timing, etc.). You need to carefully select the right startups to invest in. Hence, we fully support the view of e.g. Fabrice Grinda, who talks about a strategy of ‘informed spray and pray’.

5. Getting too little stake (too high valuation) – or the opposite: taking too much – and leaving founders without enough incentive

For some reasons we see both happening: startups that attracted funding at valuations that are – in our view – way too high, as well as startups that gave away such a large portion of their equity even before a Series A round that it hurts them in future rounds too much. Both are wrong:

If a very early-stage startup did a great job a pitching an idea at a high valuation, the startup needs to grow into that valuation (or actually beyond that valuation) for the next round. And the later-stage you get, the less it is about a believe and the more traction you need to show. Down-rounds are terrible for the morale of the investor base (and the cooperation between the investors and the founders). Even more, once you fail to live up to the promise that the early investors believed in, you are not likely to be supported (e.g. with further cash) if the valuation was set very high initially.

If a very early-stage startup diluted already e.g. 35% for EUR 100k, such startup is stuck for next rounds as well: with EUR 100k it is likely to be required to raise very fast again, but the team already diluted too much. As professional investors in early-rounds (Seed, Series A) always require having a team with a sufficient stake that motivates them, this will be a complicating factor to raise.

Our advice is always to work in a very capital efficient way: run efficient operations, and get early traction without too much cash being burned. Let your cash-out grow with the proof-points that you have set for yourself (typically client and revenue growth). If you go out to raise your first ‘professional’ round with VCs, they typically like it a lot if a team has only diluted up to 10% in angel funding rounds, and they are OK-ish up to 25% dilution prior to their investment.** A convertible loan could be a good option to look into.

6. Taking on whole investment individually (if you believe in the need for a team at a startup, why do you think you can invest all by yourself?)

Actually, there are two main reasons why it is important to work with co-investors. First of all, the knowledge and communication: it is very difficult as an angel to know about all relevant aspects of a company to evaluate the proposition properly, to support the team on the way and to be able to handle the communication independently (if you have a tough topic to discuss, it will always be you against the team).

Secondly, as getting to a next (funding) phase typically takes 1.5-3x more cash than expected, it isn’t comfortable for an angel to be the individual that is looked at when more money is needed. These decisions and negotiations are tough all by yourself. And if you require to diversify as well and need at least 10 startups in your portfolio, what if all of those look at you for a bridge round to get to the next stage? Ouch.

7. Not knowing the potential (or absence thereof) (can it scale, market size big enough, do target customers want this now?)

We believe that, even though it might be a very early-stage startup, a few assessments should be made before making an investment:

- I already discussed the importance of the team above, but in early stage investments we at least require 2 skills to be embedded in the founders: tech/product development and sales/marketing.

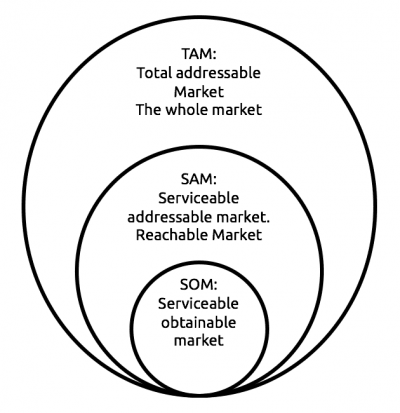

- In order to make a big exit, the (reasonably obtainable) size of a market should be big enough. We use the TAM, SAM, SOM approach for that. Both top-down (% of current market size in EUR) and bottom-up (# units to sell to # clients at certain price).

- Then we look at what it may require in terms of sales and marketing efforts to get there. Long vs short sales cycles, direct vs online sales, etc. I always like this slide by Greylock, showing that you need to understand which sales approach is required to sell at a certain price.***

- Understand the competition and their offerings: knowing how a startup aims to differentiate from the existing players in a domain improves your understanding what it takes to win a certain market share significantly.

All of these questions can be asked, even for pre-MVP companies, and all of these questions can be answered by spending some time with the team and on Google.

Also important to ask yourself: What can the exit valuation (realistically) be? What are normal exit multiples in the applicable market; which stake will I obtain; which dilution because of future rounds should I count on? In my view, some angels have an optimistic view on exits because of skewed information: you will often see press releases about the successes, but hardly any about the failures.

8. Deteriorating communication (term sheet -> investment -> champagne -> great first shareholders meeting -> missed reporting -> missed targets -> no information -> angry investor -> unpleasant situation -> dead startup)

The first 7 mistakes primarily pop up before making the investment. This one is primarily an issue after contracts have been signed and money has been wired. This one is also one that I think startups should be very keen on to monitor well, and they can. In my view:

- Startups should use a fixed reporting cycle to inform their investors (whether that is weekly, monthly or quarterly, and which content you share – that’s all up for discussions between the founders and the investors). You cannot start reporting when you feel you require some additional cash.

- Reports and meetings should be very transparent about the good and the bad. Trust perhaps is even more important than achieving certain targets.

- If you believe some parts of the communication are not going as smoothly as they should, there probably is some discomfort on the other side of the table as well. Try to address the process and the relationship in addition to just the contents. Open up discussions by asking questions and listen to the other side of the table. Don’t judge immediately, but listen, but after listening, be very clear and direct on your own views. Not saying what you think is even worse (on both sides).

- If things really go bad communication-wise, try everything you can to get back to the positivity that you need. This may also mean to get an objective third party into a session to solve it.

I am sure there are more mistakes to make… We highly appreciate initiatives as Angel Academy and Angel Investment Tour that also address these topics. We like to cooperate with angels as well as VC funds on potential co-investments. What counts for angels counts for us as well: the more knowledge, experience and network we have at the table, the higher the chances on success for our portfolio companies. Feel free to reach out.

Let me finish up how I started: I can only honor angel investors for the early-stage investments they dare to make. And a bit selfish – I admit: without them there would be significant less qualified startups for us to invest in.

This article was first published on the Peak website, but feel free to drop any comments with e.g. other ‘angel mistakes’ on the Linkedin post

* Or she naturally! – I am a big fan of diversity and equal opportunities, but I just didn’t want to extend this post too much…

** Naturally, certain startups like in hardware or very complex systems require a lot of cash initially, so these numbers may not always be applicable.

*** This assumes that a product scales (i.e. one product to many markets, instead of many products to one/more markets), as I believe that companies with products which do not scale should not anticipate venture capital to easily. And if a startup should not look at venture capital, an angel investor anticipating an investment should not anticipate the big exit outcomes which venture capital looks at.